Oil Spills

Oil Spills

adapted to HTML from Australian Institute of Petroleum with permission Oil spill prevention

Oil spill combat

Combat Techniques

How Dispersants work

see also Fuels..

see also Offshore Oil Drilling...

see also Oil Refining...

see also Oil Deposits...

see also Marine Oil Exploration...

The petroleum industry's safety record of handling oil and its products in Australia has been excellent and has been maintained throughout the last two decades of rapidly increasing volumes produced and transported in national waters. Oil spills from offshore production have been insignificant and, while there have been some spills arising from shipping accidents, none has had a lasting adverse impact on the marine environment.

Nevertheless the Australian oil industry, aware of a concern about the possible impact of oil spills on the marine environment, has stepped up its efforts to protect the ecosystems surrounding its operations. Defence against potential marine pollution is a combination of prevention and cure. In addition to the introduction of more rigorous inspections and safeguards on all its installations and tanker fleets, the industry has established, one of the best equipped marine oil spill response and training centres in the world. Sources of the oil in the sea

The risks and responsibilities associated with oil in the sea should be put in their true perspective.

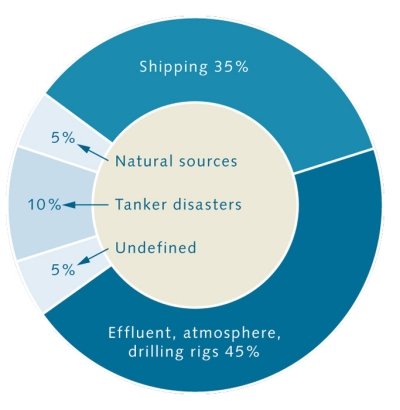

By far the highest contributor to oil in the ocean (about 30 per cent) results from a mix of materials and wastes which make up urban run-off and the discharge from land - based industrial plants. These materials reach the sea via storm water drains, sewage outfalls, creeks and rivers. Another seven per cent is oil which seeps naturally out of fissures in the sea bed. Oil and tar stranded on the beaches of South Australia and Western Victoria, for instance, was first noticed by European settlers during the early 1800s. Now it is known to come from cracks in the ocean seabed and is particularly noticeable after earth tremors in the region.

15 per cent of the oil in the sea is directly attributable to the world's oil industry. Two per cent of this occurs in spills during the exploration and production phase from rigs and platforms, and 10 per cent is attributable to accidents involving oil tankers.

Another 35 per cent occurs during the operation of vessels other than those used by the oil industry. Usually these are cargo vessels which may be involved in collisions which spill fuel oil or they may discharge waste oil from ballast tanks during a voyage.

The remaining 9 per cent of oil in the oceans is absorbed from the atmosphere.

Oil spill prevention

Statistics show that historically the oil industry is directly responsible for only a small proportion of marine oil spills, the oil companies - individually and collectively - do not take the risk of spills lightly. There are strict regulations governing all facets of their operations from the exploration / production phase through to the delivery of refined petroleum products.Exploration & production:

Almost 1,100 wells have been drilled and approximately 3,100 million barrels of oil have been produced in coastal and offshore Australia. Only about 600 barrels have been spilt in the marine environment from exploration and production operations. This is equivalent to the volume contained in a garden swimming pool and taken over a period of 25 years.

Most of these spills have involved less than 19 barrels of oil and in only a very few cases has the oil reached the shore. In Australia the majority of offshore exploration and production wells are drilled using water-based drilling fluids. In the special instances when oil based fluids are needed, strict control of the well circulatory system ensures that no oil from the drilling fluid is discharged into the sea. In addition, to cope with any sudden influx of pressure from an underground reservoir, every well drilled is fitted with a series of valves called blowout preventers. These immediately shut off the oil and / or gas flow in the event of an emergency to prevent hydrocarbons reaching the surface in an uncontrolled rush. As a result of improved technology, blow outs are virtually a thing of the past.

Above the water line, special deck drains on each rig and platform collect any waste fluids and channel them into settling tanks where oil is separated out, put into containers and sent to shore for treatment and disposal.

The Australian petroleum industry is a world leader in the treatment of water produced with oil through production wells offshore. Innovative technology includes the use of hydrcyclones and air stripping techniques to ensure the hydrocarbon content of formation water discharged into the sea is well under the Government regulatory limit of 30 parts per million.

Coastal petroleum facilities:

All production and loading terminal facilities and refineries and land are subject to strict government environmental protection policy requirements concerning the purity of water discharge into the sea. Oil companies ensure their discharges are well under the limit of 30 parts per million in water. Oil transport: Undersea oil pipelines are wrapped in special coatings to prevent corrosion and they are provided with an outer protective coating of concrete which also gives the line sufficient weight to keep it on the ocean floor. Often these lines are buried beneath the seabed as an additional safeguard.

The integrity of oil tankers is more difficult to control because the business of tanker operations is complex and fragmented. Oil company-owned vessels make up only about 15 per cent of the world fleet. Oil company-chartered tankers add another 20 per cent.

The vessels under oil company control are subject to stringent checks and regulations concerning structural integrity, safety, maintenance and crew training. Unfortunately, not all tanker owners, charterers and countries registering tankers have the same high standards. Hence vessels vary in quality and in the degree of maintenance and crew competence. However, oil companies are working with ship certification societies, insurers and the International Maritime Organisation to impose stricter control and inspection of all tankers and their operations around the world. Through rigorous vetting procedures, Australian oil companies seek to ensure that only vessels of high quality are engaged for the trade in oil and petroleum products in Australia.

Vessels owned and operated by the oil companies in Australia are subject to stringent operating and maintenance requirements. A number of designs have been introduced for new vessels - including double hulls and mid-deck tank designs - to minimise oil loss from tankers in the event of a serious accident at sea.

In the USA, the Oil Pollution Act (1990) has made it mandatory for all tankers built after June 1990 to have double hulls if they are to enter US ports. However, in other countries there is likely to be further debate on design alternatives before regulations are formally adopted governing construction of new vessels. The IMO and oil industry-funded researchers are also investigating safety measures that can be applied to the existing fleet. These include a redesigned ballast tank system, and a vacuum system which, in the event of a ruptured hull, causes water to enter rather than oil to spill out.

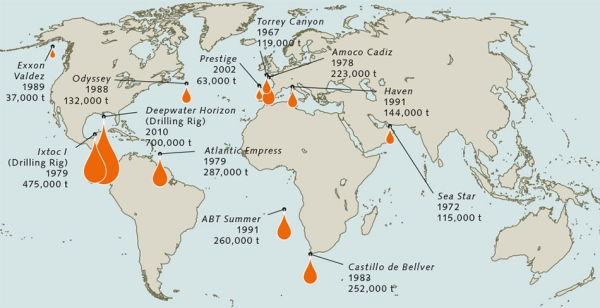

Major Spill Locations:

Oil Spill Combat

If, despite all precautions, an oil spill does occur off Australia's coastline, the oil industry in association with government agencies, is well prepared to minimise its impact on the environment.Organisations: Australia has three interconnected oil pollution response organisations - the Australian Marine Oil Spill Centre, the Marine Oil Spills Action Plan, and the National Plan to Combat Pollution of the Sea by Oil.

Australian Marine Oil Spill Centre Ltd (AMOSC): is wholly owned subsidiary of Australian Institute of Petroleum Ltd and is totally managed and funded by the Australian oil industry. There are eleven participating oil companies: Australian Petroleum Pty Limited, BHP Petroleum Pty Ltd, BP Australia Ltd, Esso Australia Ltd, Hadson energy Ltd, Mobil Oil, Australia Ltd, Santos Ltd, The Shell Company of Australia Ltd and Woodside Petroleum Ltd.

The Centre was established in 1990 to provide the equipment and trained personnel required to respond to a major oil spill off Australia's coasts. Based on Corio Bay, near Geelong in Victoria, it houses over $10 million of oil spill combat equipment and materials. This gear and the trained staff are on call 24 hours a day and they can be at the scene of a spill anywhere off Australia's coasts within 12-24 hours of being called out.

If additional back-up is needed AMOSC can call on international aid from a similar organisation based in Singapore (East Asia Response Ltd) as well as the world's largest spill organisation (Oil Spill Service Centre) located in Southampton, England. The latter has its own cargo plane on standby and can be at most locations within 48 hours of receiving a call.

AMOSC also has a purpose-built training centre where regular courses are held in oil response techniques. The Centre trains between 200 and 300 oil industry and government safety personnel each year. Marine Oil Spills Action Plan (MOSAP): was established by the oil industry in 1971 to enable an individual company to obtain assistance from other companies in combating a spill larger than it can handle with its own resources. Like AMOSC, MOSAP is supervised and funded by the oil industry through the Australian Institute of Petroleum.

The industry has provided equipment and clean-up materials at each port around Australia where oil is handled in bulk. A minor spill will be handled by the oil company concerned using the equipment available to it at or near the site. MOSAP is activated if a spill is beyond the capability of the company concerned.

If the spill is of major proportions, contact will be made with AMOSC and the Australian Maritime Safety Authority for assistance.

National Plan to Combat Pollution of the Sea by Oil (NATPLAN) has been in operation since October 1973. It is a combined effort by State and Federal organisations and the oil industry. Oil spill combat equipment is provided at various locations round Australia and a training program is conducted by the Australia Maritime Safety Authority. Funding for NATPLAN is based on the 'polluter pays' principle and a levy is placed on commercial shipping using Australian ports. These funds provide for the maintenance and administration of the Plan and allow for a contingency to cover costs not attributable to the polluter, or which the polluter is unable to meet.

Combat Techniques

No two oil spills are the same because of the variation in oil types, locations and weather conditions involved. However, broadly speaking, there are four main methods of response.- Leave the oil alone so that it breaks down by natural means.

- Contain the spill with booms and collect it from the water surface using skimmer equipment.

- Use dispersants to break up the oil and speed its natural biodegradation.

- Introduce biological agents to the spill to hasten biodegradation.

Often the response involves a combination of all these approaches.

Natural dispersion: If there is no possibility of the oil polluting coastal regions or marine industries, the best method is to leave it to disperse by natural means. A combination of wind, sun, current and wave action will rapidly disperse and evaporate most oils. Light oils will disperse more quickly than heavy oils. Booms and skimmers: Spilt oil floats on water and initially forms a slick that is a few millimetres thick. There are various types of booms which can be used either to surround and isolate a slick, or to block the passage of a slick to vulnerable areas such as the intake of a desalination plant or fish farm pens or other sensitive locations.

Boom types vary from inflatable neoprene tubes to solid, but buoyant material. Most rise up about a metre above the water line. Some are designed to sit flush on tidal flats while others are applicable to deeper water and have skirts which hang down about a metre below the waterline.

Skimmers float across the top of the slick contained within the boom and suck or scoop the oil into storage tanks on nearby vessels or on the shore.

However booms and skimmers are less effective when deployed in high winds and high seas.

Dispersants: These act by reducing the surface tension that stops oil and water from mixing. Small droplets of oil are then formed which helps promote rapid dilution of the oil by water movements. The formation of droplets also increases the oil surface area, thus increasing the exposure to natural evaporation and bacterial action. Dispersants are most effective when used within an hour or two of the initial spill. However they are not appropriate for all oils and all locations. Successful dispersion of oil through the water column can affect marine organisms like deep water corals and seagrass. It can also cause oil to be temporarily accumulated by subtidal seafood.

Decisions on whether or not to use dispersants to combat an oil spill must be made in each individual case. The decision will take into account the time since the spill, the weather conditions, the particular environment involved and the type of oil that has been spilt.

How Dispersants work

Bioremediation:

Most of the components of oil washed up along a shoreline;can be broken down by bacteria and other micro-organisms into harmless substances such as fatty acids and carbon dioxide. This action is called biodegradation. The natural process can be speeded up by the addition of fertilising nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous which stimulate growth of the micro-organisms concerned.

However the effectiveness of this technique depends on factors such as whether the ground treated has sand or pebbles and whether the fertiliser is water soluble or applied in pellet or liquid form.