Ngadjon Weapons, Utensils and Shield Making

Ngadjon Weapons, Utensils and Shield Making

Ngadjonji History of the Rainforest PeopleNote: this site contains images of aboriginal people now deceased

Wooden Shield

Steps in Wooden Shield Making by a Yidinji Elder

Axe Handle

Wooden Sword

Water Bag

Boomerang and Clapsticks

Fishing Line

Natures Calendar - migration food cycles

In memory of Nungbana - Yidinji Elder

...see

also Nungbana Restoring a Stone Axehead to functional condition

Wooden Shield Making - Rainforest People Weapons and Clan Symbols

In the old days young boys would have grown up amongst the shield-making, helping their elders at various stages. Only initiated men who had become warriors made shields for their own use.

Key to Shield Provenance of Rainforest People Wooden Shields...

- Mullunburra Yidinji Clan Nungabana's personal pattern. This is the 4th shield made and painted by George Davis.1999.

- Mamu Clan Made byGeorge Davis,painted by George +Shane Barlow, 1998. May be viewed in the Millaa Millaa Museum.

- Mullunburra Yidinji Clan Made by George Davis for the Eacham Historical Society.

- Birringbarra Yidinji Clan, showing scorpion. Made byGeorge Davis, painted by Marion Davis for second exhibition, 2001

- Walubarra Yidinji Clan, showing turtles and fish Made by George Davis, painted by Marion Davis for second exhibition, 2001.<,/li>

- Mullunburra Yidinji Clan Made by George Davis, painted by Marion Davis, 2001. May be viewed in the Indigenous Library, Cairns.<,/li>

- Mullunburra Yidinji Clan Nungabana Pattern. This is one of 4 little shields, made by George Davis for his great grandsons

- Ngadjon tribe Made by George Davispainted by Shane Barlow for the Malanda Visitor's Information Centre destroyed by a fire in 2013

Halloran's Hill Shields

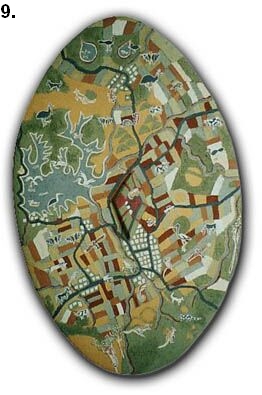

9."Landscape of the Present" The artwork on this shield represents the much changed view from Halloran's Hill in Atherton Queensland in modern timesThe shields were carved from the buttress root of a Figwood tree and painted with natural ochres from the area . The traditional lifestyle of the North Queensland Aboriginal Tribes was uniquely suited to their environment Their lives were governed by the seasonal changes and the consequent effect on the availability of food. They enjoyed a lifestyle based on hunting, gathering and fishing. Sensitive and alert to the flowering and fruiting of trees, the nesting of birds and the habits of animals, a deep respect and cooperation with the natural landscape was their heritage. Tribal movement and ceremonial activities were of necessity keyed into the seasonal cycle, the unity between the people and the land provided the basis for all aspects of life.

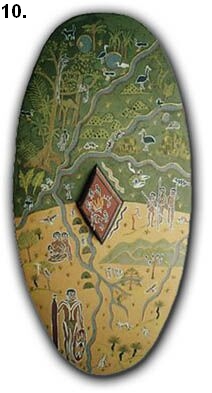

10."Landscape of the Past" The artwork on this shield is a representation of the landscape in the time before colonisation, as seen from Halloran's Hill in Atherton Queensland in ancient times

Yidinji Elder Makes a Wooden Shield

(elder is now deceased - used with permission)written by M. Huxley as told by George Davis, photographs by Duncan Ray and M. Huxley, 2000

The trunk of a Figwood soars towards the rainforest canopy

Large buttresses spread out from the base of a Figwood

In the old days, only initiated men who had become warriors made shields for their own use.

The shield blank is cut from the buttress of a Figwood tree, (Ficus albipila) called in Yidin gunagarray.

The shield is shaped and chiselled

The shield is sanded and smoothed.

Loose fibres and splinters are burnt off. Grass tree (Xanthorrhoea Johnsonii) resin, ngunuy is painted onto the shield and ignited.

A final sanding and the shield is ready for painting

Shields are painted with different coloured ochres and grass tree (Xanthorrhoea Johnsonii) resin.

The small brushes are made from lawyer cane pounded at one end, and the largest brush is a pandanus seed, pounded at one end

A white sap from a secret tree is mixed with a little saliva and painted on with the ochre, which makes the ochres waterproof.

Symbolically the shield is a bora ground. A groups’ camp position at warrama (intertribal corroboree) was relevant to the direction of their home country and the shield markings denoted where a person came from, like a flag. Shield markings represented the portion of tribal country that the clan belonged to. This is first shield made and painted by George Davis in 1998

George’s country includes some of the lowland forests of the Goldsbrough Valley and he generously donated the wood for the shields, which comes from the buttress root of Figwood ( Ficus albipila ) which grows only in the lowland forests. This wood was once a very desirable trading item.

Getting the Wood

L to R: Owen Ray, Mamu elder Robbie Major, Margaret Huxley (seated), Bernie Viddler with pooch, Duncan Ray (George's right-hand man) and George Davis.

An assortment of wood gatherers assembled in November 1999. George said we had to cut the wood before the wet season, when the sap rises. Led by Uncle George and Uncle Robbie we set off in two four-wheel drives for the upper reaches of the Mulgrave River. In the rainforest along the river is the fig called gunagarray in Yidiny (Figwood - Ficus albipila ). Incised in its majestic roots were the imprints of shields laboriously removed in the old days by stone axe. As soon as we arrived Owen found an axe-head at the base of the tree which had probably been used in the past for this ancient task.

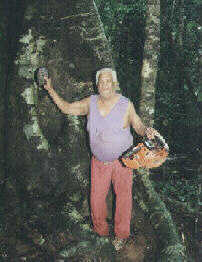

George Davis with past and present implements. An old shield scar can be seen on the tree.

George decided he could cut the wood for four shields without mortally damaging the tree, which is a managed and treasured resource.

These blocks of wood were very heavy, no matter that Bernie made it look easy. Uncle Robbie had a very effective rolling technique which worked until we reached the upward incline where the cars were parked. The blocks were loaded onto the tray of one of the vehicles and taken back to Atherton where they were stored in an airy shed for drying out. When Uncle George started to get impatient he drove around with them in the back of his car and left them sweating in the heat of the car.

Carrying out the wood

Shaping the Wood

With Shane Barlow helping, the timber is cut and dried for a few more days.

Once the wood is sufficiently dry it is put on a block, measured up and shaped using chainsaw and hammer and chisel.

Using a steel adze, Shane trims the wood back and thins it down. Next to him he has a shield made previously by Owen, Duncan and George. (left)

More sanding and chiselling, slowly the wood is fined down and the shield begins to emerge. (right)

The shield is emerging, front in good shape, side-on showing no warp.

Preparing the Surface

Loose fibres and splinters are burnt off and then the shield is sanded and scraped to get back to a smooth surface.

Resin Pot

The resin from the sap of a grass tree ( Xanthorrhoea johnsonii - ngunuy in Ngadjon & Yidiny )

is quickly painted onto the shield

and then ignited.This acts as a wood-sealant and primer for later painting.

Duncan is enlarging the handle hole by burning with red-hot coals.

George and Duncan give the shield it's final sanding.

Painting the Shield

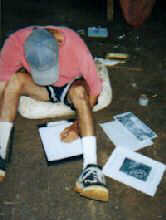

With a photocopy of the Ngadjon shields which embellished the Australian old five pound note

(Uncle George says the design on one of the two shields is the same as the clan markings for the Ngunyinbarra clan of the Ngadjonji)

(**webmaster note: the original shields sit unrecognised at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra **)

Aunty Emma's permission was given as the oldest clan member, for the use of this design.

Shane works out the pattern.

The pattern is then chalked onto the shield.

This photograph shows the complexity of the aboriginal artists' palette. The smaller brushes are made from lawyer cane pounded at one end to make a soft brush, if a finer brush is required the lawyer cane is split. The largest brush is made from a pandanus seed, pounded at one end.

Fine ochres were a sought-after trading article amongst the rainforest Aboriginal people. The white ochre comes from the Walsh River country, the yellow is always referred to as Ngadjonji yellow and comes from the clay pebbles below the Malanda Falls. The resin is from the grass tree ( Xanthorrhoea johnsonii ). The white ochre has been scraped with a small marsupial jaw bone. The other ochres are ground with rocks.

A white sap from a secret tree is mixed with a little saliva and painted on with the ochre, this makes the ochres waterproof.

Yellow, then red are painted first,

followed by the whiteand finally the black.

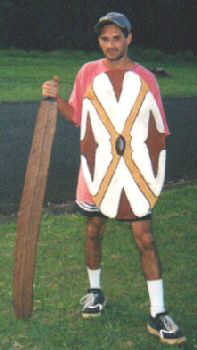

Shane with the finished shield belonging to the Ngunyinbarra clan of the Ngadjonji (whose land extended from the Russell River to Lamins Hill), which he helped to make, and the traditional sword.

.

Eddie Mitchell's Ngadjonji clan markings, for which he kindly gave us permission, chalked in, the Ngunyinbarra Ngadjonji shield and Uncle George with an unfinished shield of Yidinyji design

The Shield on Display

On Tuesday 29th February 2000 a small ceremony was held at the Malanda Environment Centre where the shield was received by the Elders and mounted as part of the display of Ngadjonji History and Culture at the Centre.Ngunyinbarra Ngadjonji Elder Emma Johnston (right) who accepted the shield on behalf of her Clan and Tribe and allowed it to be included in the Exhibit; Yidinyji Elder and Uncle to the Ngadjonji, shield-maker George Davis (left); Emma's grandson, Ngadjonji artist Warren Canendo (front) - under the shield in position in the Ngadjonji Exhibit.

(**webmaster note: the Environment Centre was burnt down in 2013 and the shield was incinerated, some years later The Malanda Falls Visitors Information Centre was built as a replacement. The Centre won a World Heritage Wet Tropics "Cassowary Award" and a Certificate of Excellence from Trip Advisor in 2016 and features the Ngadjon People of the Rainforest**)

Making an axe handle

Materials used for making a stone axe handle: Stone for axe-head, lawyer cane handle and binding.

Grass Tree resin used to adhere the handle to the axe

Finished stone axe

Making a Wooden Sword

George binds the handle with

bush string for a good grip.

George binds the handle with

bush string for a good grip.

Making a Dugubil (waterbag)

written by M. Huxley as told by George Davis, photographs by Duncan Ray and M. Huxley, 2000

Nungabana cuts and peels bark from walguy - maple silkwood (Flindersia pimenteliana). To avoid ringbarking, the bark is usually taken from only one side of the tree. The bark is soaked then heated to increase flexibility, and folded down the middle. Then it's cut, folded and sewn down the sides. The thread is made from split and treated bugul - fish-tail lawyer cane (Calamus caryotoides).The thread must be flexible for knot tieing. The handle is then sewn on. The dugubil - water bag is finished by plugging the corners with heated beeswax mixed with charcoal and rubbing the mixture on the stitches. It is then sealed by painting with a softer wax mixture. A Dugubil was used for carrying anything the people wanted to keep dry, for example the firestick,wet foods like honey and in later times tobacco and pipe. Bark is cut and peeled off.

Ringbarking is avoided

The bark is heated over a fire, to make it flexible.

The bark is trimmed and folded. The sides and top are sewn.

The bags can be used for transporting food and supplies.

Boomerangs and Clapsticks

Making Fishing Line

Bark is harvested from the Red Leaf Fig to make fishing line

George is showing how to make a fishing line. The finished fishing line is on display at the Malanda Falls Visitor's Information Centre

Nature's Calendar

Today, most of us are ruled by alarm clocks and the calendar. The Mullunburra calendar noted the natural events of the forest. The appearance of animals, the flowering of plants - many of the forests natural cycles - told the people what foods were ready to gather. The judulu (brown pigeon) call told the women that the jumbun grub was ready. The falling fruit of garrangar (fruit vine) meant the scrub turkey eggs were available. People generally ate anything but movement was dictated by where the staple foods were. There used to be a lot of cassowaries around but since the 1940's the scrub has deteriorated. As early as 1941 George remembers running into wild pigs in the rainforest.

The Migration Food Cycle - The Yidinji Seasons

Nyanbirr

...wet season January through May Head up the valley - Scrub turkey's nest for eggs White-tailed rat camps in hollow logs; easy to find and kill Flying fox - hit with a stick. Men hunt for tree kangaroo, possum, wallaby, cassowary and birds. Women and children collect yellow and black walnut and black pine. Excess is wrapped in ginger leaves and placed in a cool streamYiwai

...winter June and July Start back to the coast - Scrub python eaten mainly in Winter; grubs and brown and black frogs - part of winter diet - Eat yams and cycads. When the cicada's call changes the blackpine and walnut are ready to eat. When the wattle starts flowering go down the trail to the coast. The Python is then out from hibernation and ready to eat.Nambarr

...spring August, September, October Start back to the coast - Echidna, turtles, eels and fish were easier to catch as the water dropped. Davidsonian Plum from July through to SeptemberTjukalawarr

...summer November and December Goanna and Snakes were hunted either side of winter. Eat white apple straight off the tree; gather Badil (Cycad); collect yellow and black walnut in lowlands.Nungbana was a Mullunburra-Yidinji elder 1922-2002

Nungabana (George Davis) was born in the shelter of the buttress root of a Blush Alder Tree at Gadgarra State Forest in 1922 and spent his first 12 year roaming the bush with his grandfather Gudtjoi (Jimmy Longdon) who taught him the traditional ways. Then he worked for forty years in the timber industry (still in the rainforest.)George started: Biddi Biddi Community Advancement Co Operative Soc. - which is a housing cooperative for aboriginal people on the Atherton Tableland. George was the founding President from 1971 to 1983 and still supports this organization. Dulabed Aboriginal Corporation - He is president and an elder for more than 10 years George has educated: Eacham Historical Society - George has lead field trips and demonstrated shield making. He has donated two shields for display. School for Field Studies - George lectures to students. Sport and Recreation Tinaroo - George lectures to school students about Aboriginal Culture. Mt. St. Bernards School - George lectured to students on the art of axe making and Rainforest Aboriginal Culture. State Primary School Atherton - George lectured to students on bushtucker and Aboriginal Culture. State High School Atherton - George lectured to students and has produced a book on local Aboriginal Culture. State Primary School Malanda - George lectured to students on Aboriginal Rainforest Culture. TAFE College with Sue Taylor - George lectured to students on many aspects of Aboriginal Rainforest Culture, and has lead field trips. Society for Growing Australian Plants - George has lectured and has lead a Society field trip to the Goldsbourgh area Local Police - lectured on Aboriginal Culture and is a police liaison. Centrelink Reconciliation - lectured about local Aboriginal Culture George supports: Tableland Reconciliation Group George has worked on scientific papers with: Bob Dixon - (linguist and author) Jeanette Covacevich - Sen. Curator (Vertebrates) QLD Museum, Brisbane Tony Irvine - CSIRO Rainforest plants Laurie May - DNR forestry Wet Tropics - Kearneys flat park Kylie Pursche - Record story for school students to explain traditional aboriginal ways Bama Wabu - Aboriginal Rainforest Network (Wet Tropics) Nicky Horsfall - Anthropologist - Aboriginal Cultural Significance of Wet Tropics Bill Stella and Sorrel Willby - ABC film documentary on a rainforest walk down the Russell River Marcus Lane - Anthropologist Petronella Varzoon-Morel - Anthropologist George has worked with: Griffith University - he has revived a Yidinji walkway at Gadgarra creating local employment Atherton Shire Council Gallery - George has conducted several displays which were educational and well patronized by the whole Tableland Community. Heritage Trail Network, Haloran's Hill - George has created two Shield designs showing the landscape of the past and the present.

George Davis received a Cassowary Award in 2001 "George Davis has made an outstanding contribution to the survival and enhancement of tropical rainforest Aboriginal culture and heritage. George is from the Mullunburra Yidinji clan group and grew up in the traditional way under the guidance of his grandfather. He went on to spend the next 49 years traveling all over north Queensland's rainforests cutting timber."

ince retiring in Atherton, he has dedicated his time to his cultural heritage as both an artist and educator. He is widely respected in the Aboriginal community for his skill in making traditional artifacts such as shields, waterbag and boomerangs. He's also widely respected in the wider community as a true gentleman and a valued elder of the Atherton community. George is committed to community education and visits local schools and other centers to talk about his culture and share stories about the country he loves. George is also the author of the book "The Mullunburra People of the Mulgrave River" for high school students and everybody who is interested in aboriginal culture and history. As a World Heritage neighbour, George was actively involved in World Heritage management through the Landholders and Neighbours Liaison Group.

© George Davis 2000

Nungbana was a Mullunburra-Yidinji elder - The Early Years compiled by M. Huxley, 2002

Nungbana was born on the Atherton Tablelands in 1922. Nungabana was brought up under the guidance of his Grandfather Gudtjoi in their traditional country, learning a culture that has been passed from generation to generation over thousands of years. The Mullunburra - people of the stony river bed - are a clan of the Yidinji Tribe. Nungabana is an acknowledged authority on the Atherton Tablelands rainforest aboriginal tribes and one of the last of the traditional implement-makers. His country includes some of the lowland forests of the Goldsbrough Valley and this is where he cuts the wood for shields, which comes from the buttress root of Figwood (Ficus albipila) called in Yidin gunagarray. In the old days, he says young boys grew up amongst the shield-making and implement-making generally, helping their elders at various stages. After a man was initiated and had become a warrior he got his first shield made by an elder. Shield markings represented the portion of tribal country that the clan belonged to, symbolically the shield is a bora ground. A groups’ camp position at warrama (intertribal corroboree) was relevant to the direction of their home country and the shield markings denoted where a person came from, like a flag.

The Yidinji are an Aboriginal tribe whose traditional lands extend from the Cairns area along the coastal plain to around the mouth of the Mulgrave River and areas of the Atherton Tableland. The Mullunburra - people of the stony river bed - (‘Mullun’ meaning stony river and creek bed and ‘burra’ meaning to belong to) are a clan of the Yidinji Tribe. Each year they traveled back and forth along a traditional route between camps in the Goldsborough Valley and the bora grounds (warrama) behind Lake Eacham on Fullers Road. The camps were connected by tributaries of the river that gave its name to the Mullunburra. The Mullunburra-Yidinji enjoyed a lifestyle based on hunting, gathering and fishing. Uniquely suited to their environment, their lives were governed by the seasonal changes and the consequent effect on the availability of food. Distinctive aspects of rainforest culture included the holding of intertribal fighting corroborees using huge swords and shields, the regular use, after complex processing, of poisonous plants as a food source and horned shaped lawyer cane baskets made only in the Cairns to Cardwell region. Tribal movement and ceremonial activities were of necessity keyed into the seasonal cycle, the unity between the people and the land provided the basis for all aspects of life. The Mullunburra were very sensitive and alert to the flowering and fruiting of trees, the nesting of birds and the habits of animals. They knew what they fed on, where they rested, the paths they used. The arrival of gunyal (the cicada) in the clan’s traditional area heralds the start of the wet season, and the availability of the food sources of blackpine, yellow walnut and eggs of the scrub turkey. When gunyal changes his tune in song this told the aborigines the food was ready to eat, and their trek up to the Tablelands followed. The appearance of animals, the flowering of plants, many of the forests natural cycles, told the people what foods were ready to gather. The judaloo (Brown pigeon) calling told the women that the jumbun grub was ready to eat; the falling fruit of garangal vine meant the scrub turkey eggs were available.

Dreamtime

storytime.....feelings....story as told by George Davis photographs and paintings by Marion DavisIn that long ago Dreamtime (called Storytime), which is still present, the world was featureless, and the ancestral beings were both human (Gulnyjarubay) and non human (Gurrgiya). These beings made the country as they walked over it. They left stories about the places where they did things, and in the process defined Aboriginal Law, the proper way for people to live and behave. No part of the land is a wilderness, though some areas may be dangerous to unauthorised visitors. All of it is named, humanised, part of the story, reminding people of correct behavior. If you don't behave properly you get speared, and you are not welcome!

Feelings

I am related to my country. My grandfather was named after the hills, I am related ..."The spirits of the ancestors are still alive." If you know the story of the country where Gulnyjarubay (a Dreamtime being) walked, you will always know the spirits are with you, they are there, they guide you and they are the actual constitution of the presents. At the time Gulnyjarubay walked there he laid down the constitution for the aboriginal people to follow and not to break it. And most of them did not break it either. They kept with it all the time. And as far as the relation goes to the hills, well there are hills in Goldsborough but they are not actually my real grandfather. But they are my grandfathers relation.

We call them grandfathers. One of them is Badil, the other one is Bumbil. And I call them my grandfathers, along with my real grandfather. And the spirits of them, they are still there and to me they are still alive when I look at the mountains. They are there. They always will be there, till I die. My grandfather's estate is my area, it is related to me. It is like a house, it provides me with a cupboard, where I can get food and whatever I want (out of that area). My country is like my house. In every corne there is a shelf where I can get food or anything I want. I don't own my country, it owns me.

And I can go in every quarter of my land and get the food I want. I can get everything because I know where to look for it. I know where everything is: fish, carpetsnake, cycad (badil). It is like going in a store and grabbing things from the shelf. I get shelter and spiritual guidance too.

Totem Stories

Gurrgiya was an offsider belonging to Gulnyjarubay (a Dreamtime being). He started naming places from the joint mouths of the Mulgrave and Russel Rivers. As he came up the river, he was naming places as he swam along. There is one place called Muguyuru, a place where fish go to spawn on the Mulgrave River. It was there that the ancestral Gurrgiya, the khaki bream was speared through the gills.

Gurrgiya then stayed at the waterhole until he grew stronger and could continue the trip up the river. When Gurrgiya came to the Windin Falls he couldn't go further.There he met a frog, Madjurr (Mixophyes sp.) sitting at the bottom of the Windin Falls and also couldn't get over.

Then the Dreaming said: "Well, you still got the Tableland to explore". So they both turned into Currawongs, Jawa Jawa, and flew over Windin Falls. George Davis, was born with a black spot on the side of his neck, at the equivalent point at which Gurrgiya was speared in the Dreaming.

George Davis was the first half-caste born in his family-group, so his grandfather named him Gurrgiya, the yellow fella, the Khaki Bream. That's how he got his name.

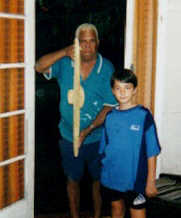

George's great grandson, Cameron Rudken

Nungabana George Gilbert Davis passed away 21 September 2002

Mr George Davis is a Malanbarra Yidinyji elder and uncle to the Ngadjonji by marriage. He is an acknowledged authority on the Atherton Tablelands rainforest aboriginal tribes and one of the last of the traditional implement-makers. Malanbarra Yidinyji and Ngadjonji were neighbours and according to Uncle George they shared trade, bora grounds on boundaries, some ceremonies and sometimes intermarried. Though they were not of the same language group, over the thousands of years they may have shared boundaries they did acquire some shared vocabulary. Traditionally many members of both tribes would have been able to speak both languages.

George has worked all his life to ensure that some of the old knowledge is preserved and in this spirit he agreed to a request by the Ngadjonji elders to make a shield for the Malanda Environment Centre and another for the Eacham Historical Society using traditional shield-making techniques and Ngadjonji clan markings. Shane Barlow and some others helped the enterprise at various times, thus acquiring some of the skills required for shield-making and some knowledge of shield markings.